EU is the abbreviation for European Union. There are 27 countries in European Union. Among them, the 10 largest countries are Germany (Population: l82,850,011), France (Population: 66,992,011), United Kingdom (Population: 66,238,018), Italy (Population: 60,483,984), Spain (Population: 46,934,643), Poland (Population: 37,976,698), Romania (Population: 19,523,632), Netherlands (Population: 17,118,095), Belgium (Population: 11,413,069), Greece (Population: 10,738,879), and Czech Republic (Population: 10,610,066).

List of European Union Acronyms

The most commonly used abbreviations about European Union are EU which stands for European Union. In the following table, you can see all acronyms related to European Union, including abbreviations for associations, airlines, funds, non-profit organizations, and etc.

European Union

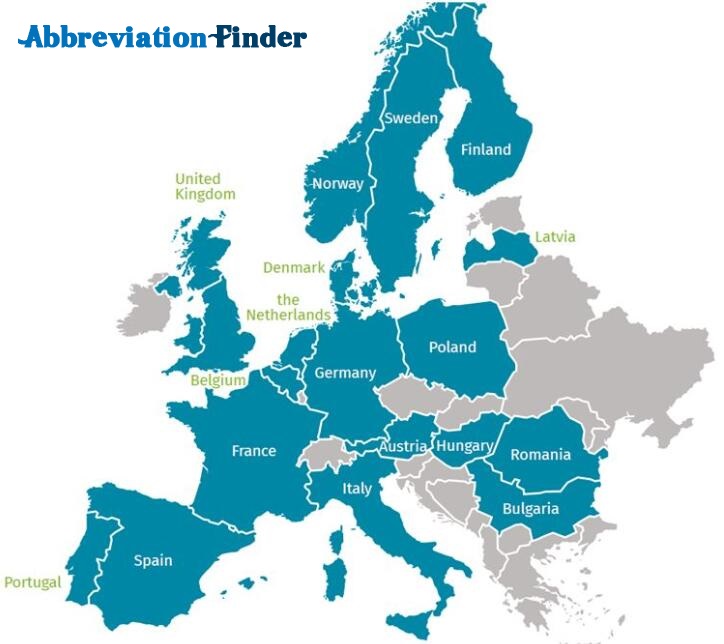

The European Union, the EU, termed the enhanced and extended cooperation between European states (27 states from 2020) since 1 November 1993 under the Union Treaty (Maastricht Treaty). The states are Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Germany (formerly West Germany) since 1952, Denmark, Ireland, Greece since 1981, Portugal and Spain since 1986, Finland, Sweden and Austria since 1995, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Czech Republic and Hungary since 2004, Bulgaria and Romania since 2007, Croatia since 2013. In 2020, the UK left the EU.

Cooperation is regulated in a number of treaties. The first came into force in 1952 and concerned cooperation in the coal and steel sector. The cooperation has subsequently been broadened and deepened in a number of treaties. This includes trade policy, agricultural policy, competition policy, as well as foreign and security policy. The latest Treaty – the Lisbon Treaty – which entered into force on 1 December 2009 represents a continuation of this development. The institutions established to lead and administer the cooperation have over the years become more and more comprehensive tasks. Questions about which states should be invited to join the EU, together with the content of the cooperation and its forms, are constantly debated and in many issues it can take a long time for the Member States to agree.

Negotiations on membership began in the autumn of 2005 with Turkey and Croatia. Croatia joined the EU in 2013. Negotiations with Turkey are ongoing. In 2005, Macedonia (now Northern Macedonia) was given formal status as a candidate country. Albania applied for membership in 2008 and became a candidate country in 2014. During the Swedish presidency in 2009, Iceland first submitted applications for membership and then Serbia. Iceland immediately began membership negotiations, but these were halted after a change of government in 2013. Serbia became a candidate country in 2012. Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo are designated as “potential candidate countries”. A further number of countries have expressed their wish to become members of the EU.

The countries that have signed the EEA agreement, including Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, have close relations with the EU. Switzerland has a pending application for membership.

The Emergence

The idea of organized cooperation between the European states was seriously aroused during the interwar period, but only after the end of the Second World War did they come to fruition. Two main directions emerged in this work. Some states wanted the European states to seize the “historical opportunity” and form a European Federation (the United States of Europe). Others wanted to increase cooperation, but let this be based on intergovernmental agreements. The result was a compromise. The cooperation would be based on voluntary agreements between sovereign states, which in certain selected areas declared themselves prepared to accept supranational decision-making. As a result of this cooperation, it was seen that the joint supranational decision-making would be so extensive that it would probably be natural to form a “union”.

The first step in this European integration process was taken through the formation of the European Coal and Steel Community (The Paris Treaty came into force in 1952). It wanted to create a body that was strong enough to coordinate operations in the coal and steel sectors so that production could be profitable, new jobs were created and the standard of living in the affected areas was raised. An important motive was also the desire to gain control over the foundations of the armor industry, especially in West Germany, so that this country could be included in Western defense cooperation without the risk of new, surprising outbreaks of revengeism and militarism. The latter claim was strongly argued by France, which became the driving force behind the new cooperation organization. This also included Italy, West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. The coal and steel community had four bodies – the High Authority, the Special Council of Ministers, Court and Community Assembly (parliamentarians) – of which the former institution had super-national powers. The Treaty on Coal and Steel was written for 50 years and therefore expired on 23 July 2002.

Treaty of Rome

The effects of the collaboration within the Coal and Steel community were judged to be so good that an expansion of the collaboration began early. The next step was taken in 1957, when, by signing the Treaty of Rome, the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Nuclear Energy Community (EURATOM) were established. After an administrative reform in 1967, the collaboration was given the collective name European Communities (EC).

The objective of the EEC (also known as the Common Market) was to achieve free movement of people, goods, services and capital. Economic discrimination on grounds of nationality was unlawfully declared. Companies could have free right of establishment within the Member States and could freely sell goods and services. (The significant difficulty of implementing this program was evident from the effort made in the mid-1980s to achieve “the internal market” by the end of 1992.)

The EEC also meant the establishment of a customs union. Goods and services could be offered without tariffs or other barriers to trade throughout the member area, and trade policy vis-à-vis countries outside the Community would also be coordinated. The goal in this area was achieved in 1968, and new members have gradually adapted to these rules. By agreement, a number of countries in other continents have come to be associated with this market.

Development assistance has previously been coordinated primarily through the Lomé Convention, originally signed in 1975, with some 70 states. Since 2000, these issues have been regulated on relations between the EU and nearly 80 states in Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific in the Cotonou Agreement.

One of the most sensitive problems in the EEC came from agricultural policy. The common agricultural policy, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), was aimed at increasing productivity, ensuring a decent standard of living for farmers, stabilizing the market for agricultural products, reducing the need for subsidies and achieving reasonable consumer prices throughout the Community. However, strong national conflicts of interest and a lack of coordination have led to widespread overproduction in a number of sectors (“meat mountains” and “wine lakes”), and support for the agricultural sector still accounts for around 40% of the EU budget.

The Nuclear Energy Cooperation Agreement (EURATOM) concerns the development of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.

Enlargement and Enhanced Cooperation

Cooperation in the three areas mentioned earlier proved attractive even to states other than the six original ones. During the 1960s, negotiations were held in several rounds with the EFTA States, however, without leading to any decision. The main contradiction was between “Europeanists”, represented primarily by France, who wanted to deepen Western European cooperation without paying special attention to relations with the United States – primarily in the military field – and “Atlantis”, represented by Britain, who wanted to maintain the strong political, economic and military ties with the United States.

Only in the early 1970s did real opportunities open for additional states to become members of the EC. Britain, Denmark and Ireland became members on January 1, 1973. Sweden had declared in 1971 that it had no intention of seeking membership, among other things, in view of the enlarged foreign policy cooperation of the Community countries in accordance with the so-called Davignon Report, which was adopted in 1970, and the planned economic and monetary cooperation (Wernerplanen 1970). Norway and Denmark were accepted as members, but felt that they had to anchor the decision by referendum in 1972. In Denmark, the supporters of the community and in Norway the opponents prevailed.

After a phase of consolidation, during which one sought to gather to speed up integration work but did not achieve any great success, one was prepared to accept Greece’s application for membership; this country became the EC’s tenth Member State in 1981. An important reason for this was the need to secure the position of democracy in Greece.

Despite free trade, trade barriers existed in the EC (technical standards, rules for public procurement and border crossing costs). Stagnation, high unemployment, missing effects of economic cooperation and increasing contradictions about both the scale and pace of continued integration work in the early 1980s urged an urgent need to move forward by expanding cooperation – new members and more areas of cooperation – and to deepen it.

Spain and Portugal became members in 1986, giving increased weight to the southern European element of the organization.

The deepening of the cooperation was presented in the so-called White Paper in 1985, which presented almost 300 proposals for concrete measures (harmonization) that would lead to the establishment of an “internal market” by the end of 1992. The plan was accepted as a basis for the further work. However, it was also required that the organization and decision-making be adapted to the new goal. To this end, a Single European Act, which came into force in 1987, was drafted.

Parallel to this internal process, the EC has since 1984 negotiated extended cooperation with the EFTA countries under the EEA Agreement (European Economic Space). An agreement was signed in 1992 but did not enter into force until January 1, 1994. The reason for the delay was that the agreement could be rewritten after the Swiss people said no to the agreement in a referendum. Liechtenstein joined the EEA Agreement in 1995.

In addition to the majority of EFTA states, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, a number of other countries made requests for closer relations with the EC. Among these were Turkey and a number of states in Eastern and Central Europe. In 1993 and 1994, intensive negotiations were held with the four membership-seeking countries Finland, Norway, Sweden and Austria. In the early summer of 1994, these negotiations were concluded, and Austria was the first to approve the agreement after a referendum. In October, Finland followed Sweden and a month later, while the result in the Norwegian referendum again became a no. On January 1, 1995, the first three countries became full members of the EU.

During the first half of the 1990s, the EU developed a special type of cooperation agreement – so-called Europe agreements – with countries in Eastern and Central Europe. The issue of continued enlargement of the EU was thus given a central place in the political discussion early on. The broadening and deepening processes within the EU have also affected the current members’ views on their own position in the organization and on its long-term goals. The contradictions are most evident between those who want to achieve a full-fledged political and economic union (for example, Germany) as quickly as possible and those who can envisage deeper cooperation where, however, individual countries have not abandoned their crucial sovereignty claim (for example, the United Kingdom). Within the organization there is also a certain power struggle between the four main organs of the Council of Ministers, the Commission,

The Union Treaty

The discussions on the deepening of the cooperation led to an intergovernmental conference held in 1991 in the Dutch city of Maastricht (see Union Treaty). After quite stormy debates, a new treaty on a European Union succeeded. The main features of this were that the previous EC cooperation should be further expanded and include, inter alia, an Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) with a single currency (1996 dubbed to the euro) and a joint central bank ( European Central Bank, ECB). The cooperation would also include a common foreign and security policy and a common defense policy, which over time could lead to joint defense as well as cooperation in home affairs and justice (including asylum issues and police cooperation).

In 1992, the Danish people voted against the proposals for expanded and deepened cooperation that formed the basis for membership in the new Union. Protests also occurred in several other Member States. However, after both Denmark and the United Kingdom were granted certain exceptions (including participation in the third stage of the EMU process) and a new referendum in Denmark took place, and after the approval of the German Constitutional Court, the treaty could enter into force on November 1, 1993.

As there was a great deal of uncertainty about the meaning of the Treaty at several points, it was written that a review conference would be organized in 1996. In order to get better equipped for this, the governments of the member states appointed a so-called reflection group. Senior officials from all Member States were commissioned to prepare all issues that would come up on the IGC agenda. Neither during the reflection group’s work nor during the Intergovernmental Conference were there any more notable conflicts.

At the same time, it emerged at an early stage that it was clear that reforms could not be reached on some of the most central areas, such as the composition and roles of the institutions, as well as on agricultural policy and the Structural Funds. Even when it came to the view of enlargement of the EU, opinions went apart. In particular, it was the complicated employment problems that could be linked to the need to meet the convergence requirements in EMU, and the enlargement issue that limited the political scope for action.

Amsterdam Treaty

When the heads of state and government met in Amsterdam in June 1997, two of the leading EU countries had held general elections. In both cases, these had resulted in a shift in power. In Britain, Labor leader Tony Blair took over as prime minister, and in France, Socialist leader Lionel Jospin became the new head of government. In the French case, the change of government was not expected to lead to any major changes in the country’s EU policy. However, expectations were higher for the new British government.

The final negotiations proceeded “in a positive spirit”. The hopes of a more positive attitude to EU cooperation, for example in the social dimension, from the new British government were met. However, it was clear early on that several of the heaviest issues could not be decided. These included institutional reforms, some budgetary issues and the reform of agricultural aid. The result was the Amsterdam Treaty, which was signed by the governments in the autumn of 1997 and came into force in 1999.

Despite a lack of consensus, including in the field of employment policy and most of the institutional reforms deemed necessary, most analysts agreed that the Amsterdam Treaty could help to broaden and deepen EU cooperation. New rules for increased “transparency” (transparency), the development of new forms of conflict prevention and security-creating cooperation, and the inclusion of the Schengen agreement, that is to say, the abolition of border controls, and the marking of citizens’ rights within the Union were seen as signs of this.

The right for a smaller group of states to deepen cooperation on certain issues (“flexible integration”) attracted great interest. “Flexibility” could, for example with reference to EMU, be seen as a solution to the problem that some member states want to move at a faster pace than others in some integration areas.

Critics saw this as a risky first step towards a progressively increasingly complicated system of varying degrees of participation in EU cooperation. This is illustrated by the creation of a “Euro Council”, in which only full members of the EMU have the right to attend and vote. However, it was clear early on that it was almost immediately necessary to begin the work of preparing a new treaty conference to deal with the many issues left after the Amsterdam meeting (Amsterdam “left-overs”). A new IGC was therefore announced in the spring of 2000, and it was hoped that at the December summit this year, it would have been possible to agree on most of the outstanding issues.

The end of the 1990s was a hectic time for the EU and its member countries. In addition to the recurring contradictions on budgetary issues, it was the implementation of the third stage of the EMU process, that is, the transition to the euro, and enlargement issues that were at the center.

With regard to EMU, the transition process was initiated on 1 January 1999 in 11 of the Member States. Outside were Denmark and the United Kingdom, which could refer to exemptions, Greece and Sweden. Greece, which did not meet membership requirements at first, later joined EMU. In September 2003, Sweden held a referendum on the introduction of the euro as currency. The result was that a majority voted against the proposal (55.9 percent no, 42.0 percent yes, 2.1 percent blank). The new currency, the euro, was put into operation on 1 January 2002.

Enlargement to the east

In the Agenda 2000 (1997) action program, the Commission presented proposals on how the EU should prepare for enlargement. In 1998, negotiations on EU membership began with a first group of candidate countries (Cyprus, Estonia, Poland, Slovenia, the Czech Republic and Hungary) and a year later with six additional countries (Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania and Slovakia). All countries except Bulgaria and Romania joined on 1 May 2004. Bulgaria and Romania joined on 1 January 2007.

Negotiations on membership began in the autumn of 2005 with Croatia and Turkey. At the same time, Macedonia (now Northern Macedonia) was given formal status as a candidate country. In 2012, this status was also given to Serbia, at the same time that negotiations began with Montenegro applying for membership in 2008. Iceland began negotiations with the EU on membership in 2010. Croatia joined as a member on July 1, 2013. A further number of states, mainly in eastern and southern Europe, have expressed requests for membership. In order to support the states that have been granted candidate status, the EU has developed a “membership program”. The EU has also developed a specific program for cooperation with other neighboring states (European Neighborhood Policy (ENP)).

The Nice Treaty and the Future Convention

When the government negotiations for the next treaty began in the spring of 2000, the whole of Europe was pressured by the continued absence of signs of economic recovery. In several Member States, declining employment levels and cuts in public social services led to political and social concerns. In part, this was channeled against the EU and against the EU’s plans for enlargement. Concerns about overly liberal policies in the area of labor immigration and the transfer of large financial resources to the new Member States were given considerable room in the public debate. In more and more countries, there was a growing demand for governments to look after national interests.

The Treaty of Nice (signed in 2001 and entered into force in 2003) established new rules for cooperation in a number of areas. The main debate was the new voting rules in the Council of the European Union (Council of Ministers), while there was agreement to complete the enlargement process as soon as possible. This time, too, the heads of state and government failed to finalize more than a small number of cases.

During Sweden’s chairmanship period in the spring of 2001, work began to stimulate a broad and in-depth debate on the future tasks and structure of the EU. At the summit in the Belgian city of Laeken in December 2001, it was decided that the next Intergovernmental Conference should be prepared by, inter alia, discussions between government and parliamentary representatives from both current and future member states, as well as from the EU institutions. The Future Convention’s proposal was presented in the summer of 2003. An Intergovernmental Conference was convened on October 4, 2003, to consider the Convention’s proposal.

Lisbon Treaty

The June 2004 European Council reached an agreement on a draft constitutional treaty for the EU. After the text was drafted by experts, the process began by which all the member states, in the manner they themselves chose, would approve the “Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe”.

After the people of France and the Netherlands voted in the referendum in 2005 in the new treaty, the heads of state and government decided that the EU should take a reflection break to consider what needs to be done to achieve the unanimity necessary for the new constitutional treaty should be able to take effect. During this period new negotiations were conducted. This resulted in a revised text of the Treaty, the Lisbon Treaty, which was signed by Member State governments in December 2007 and subsequently submitted to national parliaments for approval. This process was completed in November 2009 when the Czech Republic as the last country approved the treaty. The Swedish Parliament signed the Lisbon Treaty in December 2008.

Member Countries

| Country | Capital | Membership |

| Belgium | Brussels | 1952 |

| Bulgaria | Sofia | 2007 |

| Cyprus | Nicosia | 2004 |

| Denmark | Copenhagen | 1973 |

| Estonia | Tallinn | 2004 |

| Finland | Helsinki | 1995 |

| France | Paris | 1952 |

| Greece | Athens | 1981 |

| Ireland | Dublin | 1973 |

| Italy | Gypsy | 1952 |

| Croatia | Zagreb | 2013 |

| Latvia | Riga | 2004 |

| Lithuania | Vilnius | 2004 |

| Luxembourg | Luxembourg | 1952 |

| Malta | Valletta | 2004 |

| Netherlands | Amsterdam | 1952 |

| Poland | Warsaw | 2004 |

| Portugal | Lisbon | 1986 |

| Romania | Bucharest | 2007 |

| Slovakia | Bratislava | 2004 |

| Slovenia | Ljubljana | 2004 |

| Spain | Madrid | 1986 |

| Sweden | Stockholm | 1995 |

| Czech Republic | Prague | 2004 |

| Germany | Berlin | 1952 |

| Hungary | Budapest | 2004 |

| Austria | Vienna | 1995 |

View this article in other languages:

Deutsch – Français – 繁體中文